In 1976, the gravel-voiced American singer-songwriter Tom Waits unveiled one of his strangest and most memorable songs: The Piano Has Been Drinking (Not Me).

It appeared on his third studio album Small Change, and you can also hear a live extended version on his 1981 compilation Bounced Checks.

The song conjures the smoky atmosphere of a nightclub at closing time.

Waits begins with a melancholy piano introduction before sliding into his slurry, semi-spoken delivery. He plays the role of a late-night drunk who insists it’s the piano, not himself, that’s intoxicated.

With only a bowed double bass and his own maudlin piano for company, Waits created a woozy, surreal masterpiece.

It’s tongue-in-cheek, of course. But the image of a “drunk piano” is a fitting gateway into a less humorous truth: many of history’s greatest composers – including some of the most sublime pianists – struggled with alcohol. Their stories draw attention to the strange interplay between genius and intoxication.

Beyond The Rock ’n’ Roll Cliché

We tend to associate excess with the hard-drinking rock stars of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s:-

Keith Richards with his cognac,

Jim Morrison drowning in whisky,

Elton John candidly admitting to years lost in a haze.

But long before rock ’n’ roll, alcohol was already entwined with music. The great classical composers, architects of the great piano concertos, nocturnes, and sonatas we still play today, often lived lives that would shock even the most reckless rocker.

Franz Schubert: Wine, Song, And A Short Life

Schubert was rarely without a glass of wine.

He and his circle of friends, known as the Schubertiads, met frequently for evenings of drinking, singing, and revelry. His daily intake was staggering, measured in litres rather than glasses.

This drinking worsened his health. Already weakened by syphilis, his body could not withstand years of alcohol abuse. He died in 1828 at just 31.

Yet his piano music – such as the Impromptus and Moments musicaux – carries the bittersweet lyricism of a man who knew joy and despair in equal measure.

Johannes Brahms: Beer, Brothels, And Brilliance

As a young man in Hamburg, Brahms earned his keep playing piano in bars and brothels. These environments left a lasting mark: he remained a lifelong customer of such establishments, and beer halls became his natural habitat.

Brahms was a heavy drinker, often blunt and boisterous once lubricated. Yet he was also disciplined, composing by day after long nights of revelry. His piano concertos and intermezzi show no sign of impairment. Indeed, the tavern may have been his unlikely muse — noisy, smoky, but full of humanity.

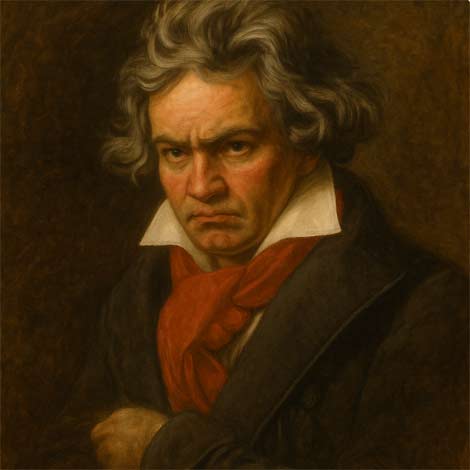

Ludwig van Beethoven: Disorderly Genius

Beethoven’s love of wine was legendary. His lodgings were littered with bottles, and he was frequently seen in a disheveled state. On one occasion he was arrested for being drunk and disorderly. When he told the officers “I am Beethoven,” they refused to believe him – his appearance was too ragged for the great composer.

Beethoven’s love of wine was legendary. His lodgings were littered with bottles, and he was frequently seen in a disheveled state. On one occasion he was arrested for being drunk and disorderly. When he told the officers “I am Beethoven,” they refused to believe him – his appearance was too ragged for the great composer.

Alcohol worsened his liver disease, which contributed to his death at 56.

Yet even through deafness and addiction, he wrote the piano sonatas that remain pinnacles of the repertoire. It seems the man was chaotic, but the piano kept its clarity.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Champagne And Chaos

Mozart adored champagne, punch, and strong spirits. Letters reveal a young man who loved jokes, pranks, and nights of drinking. Though often financially strapped, when money flowed, much of it went on lavish socialising.

This reckless lifestyle, combined with relentless work, eroded his health. He died at 35.

Yet his piano concertos of the 1780s and 1790s – playful, dazzling, endlessly inventive – suggest that whatever chaos swirled around him, the piano remained his true anchor.

Robert Schumann: From Carnival To Catastrophe

Robert Schumann was a true victim of the bottle.

In Heidelberg, after a wild night at a carnival, he staggered home and smashed his piano to pieces in a drunken fury.

Wine and champagne worsened his fragile mental health.

By his forties he was hallucinating, hearing ghostly music.

In 1854 he attempted suicide and was confined to an asylum, where he died at 46.

His piano works – from Carnaval to Kinderszenen – are mercurial, whimsical, and haunted, mirroring his own fractured psyche.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Vodka And Vulnerability

Tchaikovsky often turned to vodka to soothe his inner turmoil.

Tchaikovsky often turned to vodka to soothe his inner turmoil.

Living as a closeted homosexual in Tsarist Russia, he was torn between public expectation and private despair.

Letters describe his shame after drinking bouts, but the cycle repeated.

Yet his piano works, especially the First Piano Concerto, blaze with grandeur.

The contrast between his fragile inner life and the strength of his compositions is stark – as if the piano gave him a voice when drink left him mute.

George Frideric Handel: A Taste For Feasting

Handel was known for his epic appetite for both food and wine.

His dinner parties were the stuff of legend. He grew fat, but his productivity remained astonishing: 42 operas, 29 oratorios, countless keyboard works.

Though the modern piano was still young in Handel’s time, his harpsichord suites and concertos remain staples. One suspects many were conceived after evenings of convivial excess.

Erik Satie: Absinthe And Absurdity

In fin-de-siècle Paris, Erik Satie embraced absinthe — the infamous “green fairy.”

Living in poverty in Montmartre, he built his eccentric reputation on odd routines and heavy drinking.

The Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes, fragile piano miniatures, seem to float outside time. They are paradoxical: works of utter clarity from a man lost in a haze.

Satie died at 59, cirrhosis among the causes.

(If you would love to learn Erik Satie’s Trois Gnossienne check out this amazing course from Pianoforall Academy)

Jean Sibelius: Brandy and Silence

Jean Sibelius could drink almost anyone under the table.

His favourite beverage was brandy, often consumed in heroic quantities. Drinking bouts sometimes lasted days, followed by long silences.

Even during the period of prohibition in his native Finland, which ran between 1919-1932, Sibelius obtained cognac as a ‘medication’ by prescription.

Sibelius’s alcoholism stalled his career. After the 1920s he wrote little of substance over the course of the last thirty years of his life.

While his piano music is arguably overshadowed by his body of symphonic work, nevertheless, both carry an unmistakable sense of Nordic fire and frost.

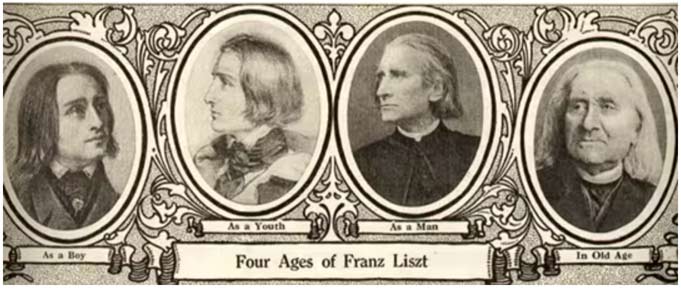

Franz Liszt: From Bacchus to the Basilica

In his youth, Liszt embodied excess: women, fame, and oceans of wine. His piano concerts caused near-riots, “Lisztomania” sweeping Europe.

But in later life he turned austere. He gave up much drinking, entered minor religious orders, and produced sparse, introspective piano works.

The flamboyant showman ended as a monkish figure, his late pieces foreshadowing modernism.

The Four ages of Franz Liszt. The Etude magazine, 1913.

The Four ages of Franz Liszt. The Etude magazine, 1913.

Igor Stravinsky: “Stra-Whisky”

Moving into the 20th century, Igor Stravinsky was rarely without a hip flask of whisky. He was so fond of it that he once quipped, in heavily accented English: “My God, so much I like to drink Scotch, that sometimes I think my name is Igor Stra-whisky.”

His modernist piano works — sharp, angular, rhythmic — show no sign of sloppiness. If anything, his fondness for Scotch kept pace with his disciplined compositional style.

Not All Drank – Some Preferred Other Escapes

While many composers fell prey to the darker sides of alcohol, others resisted.

Hector Berlioz, Richard Wagner, and Frédéric Chopin seemed immune to the lure of the bottle.

But not because they lived cleanly.

Instead, they preferred opium, which brought its own dangers. In their cases, the piano was accompanied not by a glass of wine but by the haze of another intoxicant.

The Piano : Channeler Of Music From Chaos

From Schubert’s wine-fuelled nights to Stravinsky’s whisky quips, the piano has often had a bottle resting on top.

For some, like Brahms, alcohol was woven into daily life without derailing creativity. For others, like Schumann, it hastened tragedy.

Yet through it all, the piano remained steadfast. It absorbed the intoxication of its players and transformed it into clarity, beauty, and truth.

Tom Waits joked that the piano has been drinking. In reality, the piano has always been the sober partner — forgiving, patient, and endlessly capable of turning chaos into music