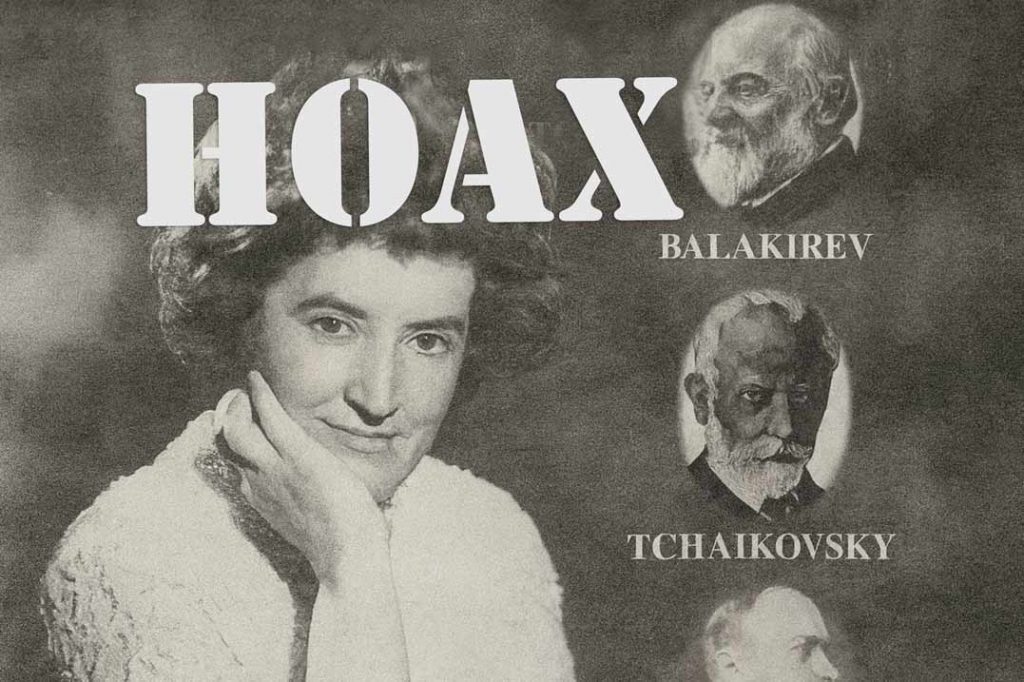

In the long history of the piano, there have been prodigies, virtuosos, and visionaries. But there has also been one of the strangest scandals the music world has ever known — the story of Joyce Hatto and her husband, William Barrington-Coupe.

On the surface, it was a tale of triumph over obscurity: a modestly known British pianist who, late in life, suddenly emerged as one of the greatest interpreters of piano music.

In reality, it was a fraud of breathtaking audacity — a hoax that fooled critics, delighted listeners, and embarrassed much of the classical music establishment.

A Pianist of Some Talent, But Little Fame

Joyce Hatto was born in London in 1928. She was by all accounts a reasonably gifted pianist. In the 1950s and ’60s she performed solo recitals across Britain and Europe, appeared at prestigious venues like Wigmore Hall and Queen Elizabeth Hall, and made a number of recordings. But she was never regarded as a leading figure of her generation.

Critics often found her playing competent but uninspired.

A 1953 review in The Times called her Mozart concerto “emotionless,” while Gramophone magazine in 1961 dismissed her Rachmaninoff concerto as “pallid.”

She supplemented her income by teaching piano privately and in schools, eventually giving up public performance altogether in 1976.

That might have been the end of the story — a decent pianist with a modest career. But then came the resurrection.

The Sudden Rise of a “Neglected Genius”

In the late 1980s and ’90s, Hatto’s husband, record producer William Barrington-Coupe, began issuing recordings on his small label, Concert Artist Recordings.

From the mid-1990s onwards, over one hundred CDs appeared under Hatto’s name. The repertoire was vast: Beethoven and Mozart sonatas, Prokofiev concertos, Rachmaninoff, Brahms, Mendelssohn — even marathon projects like complete cycles of Chopin Études and Liszt’s Transcendental Études.

The story was irresistible: here was a pianist, long overlooked, producing a flood of masterful performances from the seclusion of her home studio while battling cancer.

On early internet forums, listeners began to praise Hatto as a hidden treasure. Critics followed. By the early 2000s, glowing reviews appeared in magazines. The Boston Globe hailed her as “the greatest living pianist that almost no one has ever heard of.” In 2006, Radio New Zealand devoted an hour-long special to her artistry.

Sales of Hatto CDs climbed. For a woman who had once been a footnote, it was an astonishing reversal of fortune.

The First Cracks in the Façade

Not everyone was convinced. In 2005, a sharp-eared musicologist noticed something strange: Hatto’s recording of a Chopin piece seemed identical to a 1993 recording by the Italian pianist Carlo Grante — down to an identical misreading of a chord. He posted his observation on an online forum, but at the time it attracted little attention.

Others were puzzled by the mysterious conductor “René Köhler,” credited on many of Hatto’s concerto discs with the Warsaw Philharmonic.

The backstory supplied for Köhler was dramatic: a Jewish child prodigy barred from studying in Warsaw, his hand injured by a German soldier, deported to Treblinka, then imprisoned in a Soviet labour camp until 1970, only to emerge as a conductor.

Critics repeated the tale, marvelling at his resilience.

It was all fiction. René Köhler and his orchestras were figments of Barrington-Coupe’s imagination.

The Truth Emerges

The hoax only unravelled in 2007, a year after Joyce Hatto’s death from cancer.

A critic at Gramophone magazine put one of her CDs into his computer. The CD player’s track-recognition software identified the performance as not Hatto, but another pianist entirely. Further comparisons revealed that many of Hatto’s recordings were, in fact, copies of commercial CDs by other pianists.

Barrington-Coupe had used his production skills to duplicate and, in some cases, digitally manipulate these recordings — adjusting tempo, equalisation, or splicing sections — before rebadging them as his wife’s work.

The pianists he copied were often excellent but not household names, making the fraud harder to detect.

When confronted, Barrington-Coupe admitted to the deception. His defence was that he had wanted to comfort his ailing wife, to give her the recognition she never received in life.

But the scale of the deception went far beyond a private gesture.

Embarrassing the Experts

The revelation was devastating — not least for the many critics who had heaped praise on the supposed Hatto recordings. Esteemed magazines had called her interpretations “revelatory” and “magisterial.” Now they were forced to admit they had been praising performances by pianists they had previously overlooked.

It was one of the most embarrassing moments in classical music criticism.

If the experts couldn’t tell the difference, what did that say about the authority of their judgment?

What Price the Fraud?

Despite the scale of the hoax — more than a hundred fraudulent recordings sold internationally — William Barrington-Coupe never faced criminal prosecution.

Legal experts suggested it would be difficult to prove fraud beyond reasonable doubt, especially since some of the copied pianists did not wish to pursue charges.

Barrington-Coupe was publicly disgraced, but he lived out his remaining years quietly, dying in 2015.

A Strange Legacy

So what are we to make of Joyce Hatto?

She was not a great pianist, but neither was she talentless. She was real: a London-born musician who performed, recorded, and taught for decades. Yet her name is now synonymous not with her own modest achievements but with her husband’s astonishing fraud.

The Hatto scandal reminds us of both the piano’s power and its vulnerability. Recordings can inspire and deceive. Reputations can be built — and destroyed — on what people hear through a pair of speakers.

For pianists and learners today, there is a gentler lesson. No fraud is needed. The piano itself, in all its honesty, gives back exactly what you put into it. Whether you are practising a Chopin Étude or playing a few simple chords as you learn the accompaniment for a favourite song, the joy comes not from fame or false acclaim, but from the authentic connection between your hands, the keys, and the music.